The Roots of a Revolution

It was a balmy evening in 1947, the kind where the air carried whispers of promise and the distant hum of a train echoed faintly in the background. In a smoky club on Beale Street in Memphis, a young man named Thomas “Blue” Carter gripped his guitar like it was an extension of his soul. His fingers danced over the strings, weaving a sound that seemed to shimmer in the air, blending the gospel rhythms of the church with the raw, pulsating energy of blues.

Blue wasn’t just playing music; he was telling a story—a story of joy, pain, resilience, and love. The audience in the tiny club, a mix of working-class African Americans, swayed to his rhythm, their spirits lifted by the syncopated beat of the drums and the sultry cries of the saxophone. They were no strangers to hardship, but in this music, they found solace. It was something different—something new.

This new sound wasn’t confined to Memphis. Across the nation, in bustling cities like Chicago, Detroit, and Los Angeles, musicians like Blue were experimenting with the blending of gospel harmonies, jazz improvisations, and the blues’ heartfelt narratives. In Chicago, a young woman named Etta Mae Brown sang her heart out in a club on the South Side, her voice a smoky mix of vulnerability and power. Her band’s upright bass thumped in perfect sync with the kick of the drum, creating a groove that made even the most stoic listener tap their foot.

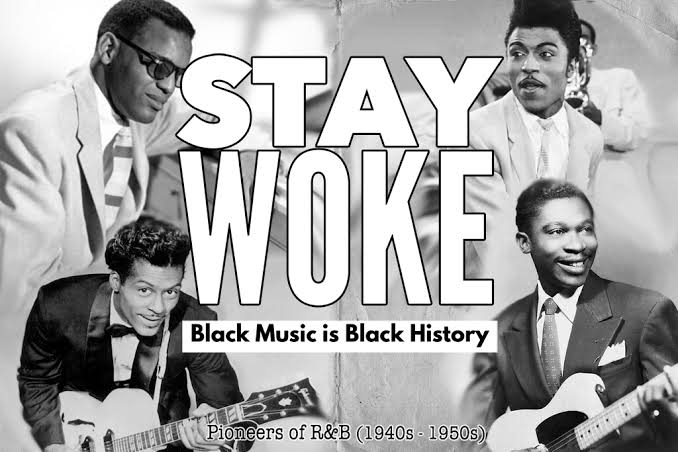

But R&B, as it would later be called, was more than just music. It was a cultural revolution born in the heart of the African-American community, where church hymns met the juke joint. It was music for dancing, for celebration, and for protest. Its lyrics spoke of love and heartbreak, yes, but also of freedom and identity in a country where racial segregation and inequality were everyday realities.

Blue’s best friend, James “Pops” Turner, worked as a railroad porter by day and played piano in a traveling band by night. “You know,” Pops said one evening, sipping on a glass of whiskey after their set, “this music feels like freedom. It’s the sound of us breaking our chains, one note at a time.”

It was true. Radio stations in cities with large African-American populations started playing this new music, and records began to fly off shelves. By 1949, Billboard would officially name it “Rhythm and Blues,” giving a genre to the sound that had been steadily growing for nearly a decade.

Back on Beale Street, Blue finished his set with a song he called “Train to Freedom.” The audience roared, clapping and cheering as if they knew they were part of something greater than a single performance. What they couldn’t know was that this music, their music, would soon break out of the clubs and into the mainstream, changing the sound of America forever.

And so, R&B was born—not just a genre, but a movement, a rhythm that carried the hopes, dreams, and defiance of a community determined to be heard.